|

SYDNEY CLARKE HOOK

(1857–1923)

Introduction

In October 1909, an advert appeared The Evening Standard in which a

gentleman sought to rent a large country house with two acres or so of land,

with the option to buy the freehold, if possible. An unremarkable request in

itself perhaps, but one revealing to students of popular literature, for the

gentleman who placed that advert (and who was successful, incidentally)

turned out to be the star author of the Amalgamated Press, then an enormous

organisation dedicated to the publication of story papers, comics and

magazines. The writer’s name was Sydney Clarke Hook, a relative of the

highly regarded artist, James Clarke Hook (1819–1907), and it is fair to say

that, were one to indulge in a little fanciful speculation and imagine some

unfortunate accident prematurely ending the lives of both S Clarke Hook and

the up-and-coming writer Charles Hamilton in a single moment in say, 1909,

then the fortunes—if not the very survival of the then burgeoning

Amalgamated Press—would have looked very shaky indeed. True, that large

organisation had scores of writers (some of them gifted professionals,

others workaday hacks) on their books, but there simply was no one who could

have stepped forward into the breech long-term to fill S Clarke Hook’s

position: at that time he was their greatest money-spinner through his

stream of humorous and exciting tales of adventure, and the coup de grace

would have been delivered by a simultaneous loss of his younger contemporary

Charles Hamilton, who was steadily breathing new life into the school story

genre through the Magnet and the Gem.

Fortunately for all concerned, no such scenario ever took place—but its

consideration does carry with it an important real-life corollary: Charles

Hamilton went on to find great fame (and some fortune) in the following five

decades, remaining something of a niche force to this day, largely owing to

Billy Bunter and the wonderful supporting cast of Greyfriars School. Very

different though has been the fate of S Clarke Hook’s famous trio Jack, Sam

& Pete, which has virtually disappeared without trace—together with their

creator’s name.

Yet the erstwhile popularity of these characters cannot be overestimated:

at the height of their fame, actors were employed to impersonate them during

the summer holiday period and to stroll along various well-frequented

seafronts to advertise the Marvel (in whose pages the rumbustious

trio’s weekly adventures were recorded) in order to boost sales. Indeed, as

late as 1919, a silent movie was made of their adventures called simply

Jack, Sam and Pete, with follow up films planned—though it is not known

whether these others were ever made. Yet according to the researcher Bill

Lofts, their creator died four years later in 1923 in a Bournemouth nursing

home, heartbroken at the loss of his characters’ popularity and their

falling out of fashion.

So, what went wrong—and why?

Jack, Sam & Pete

The tales

In the realm of story papers probably only Henry T Johnson and Charles

Hamilton himself were more prolific than Sydney Clarke Hook, who wrote under

many pen-names (viz, Hampton Dene, Maurice Merriman, Edgar Hope, Captain

Lancaster, Captain Maurice Clarke, Innis Hale, Owen Monteith, Ewen Monteith

being some of them—the list is almost certainly incomplete). It is worth

noting that Clarke Hook also occasionally wrote entertaining school

stories—the Stormpoint series serialised in the Gem in 1907

and in the Boys’ Friend Library there were four long tales in issues

20, 130, 321, 456—but these were not really his forte; action and adventure

in wild or mysterious foreign parts with an admixture of comedic slapstick

was what he really excelled in. And as with Hamilton, there is a discernible

bipolarity of approach: stories are either essentially dramatic with

subordinate comedic scenes for light relief, or essentially pure comedy.

The distinctive difference however between the two writers lies in their

use of description: in Hamilton it is detailed, sometimes repetitive and

always present, even in the smallest sub-scene, whereas in Clarke Hook’s

universe it is nominal, sparing and perfunctory, the action usually being

‘described’ or inferred through live (and often lively) dialogue. Characters

are often introduced after they have appeared through spoken

reference or direct address; they vanish just as quickly. Dialogue is the

conduit of much of the action, be it dramatic or comedic, and Clarke Hook is

very good at this, but it does make the reader pay close attention, for it

is easy to miss an important detail this way—something impossible in

Hamilton’s leisurely and even hypnotic style. There are no surprises in

Hamilton; there are many in Clarke Hook.

It would be unfair though to give the impression that Clarke Hook is

unable to supply atmospheric descriptions when required; when they do

appear, you notice them. Take for example this unusually expansive opening

from a once very famous early tale in the Marvel called The

Phantom Chief, from 1904, reprinted many times:

‘A stormy day had changed to a stormier night;

distant thunder rolled through the black havens, echoing amongst the

towering peaks of the Andes where that vast chain ends in Patagonia, the

land of giants and dwarfs. And here, on the mountain slope, sheltered by a

huge boulder from the gusts of wind which howled mournfully amongst the

ragged crags, stood the three comrades—Jack, Sam and Pete.

At the base of the mountain lay a forest of

cedar and cypress trees, where the howling of wolves could be heard, and the

roar of the puma and the ocelot, as they slunk away to their lairs to escape

the rising storm.

Between black boulders raged a mountain

torrent, barring the comrades’ further progress, for no man could have

crossed those rushing waters which were churned to a mass of foam as they

tore round the jagged rocks that rose above the surface of the flood.

As the storm rolled up, the lightning played

more frequently, and angry jags of forked lightning darted towards the

earth.’

This is the work of an accomplished writer who not only knows how to set a

scene, but how to do so in a way that rivets our attention. And with what

comes out of that storm he does not disappoint.

The first tale of the comrades (The Eagle of Death—Clarke Hook

always had an arresting ear for a good title) appeared as far back as in

1901 in the Marvel; the last one written by their creator appeared

posthumously in the BFL in 1924, called Volcano Island. Though long

past both their sell-by date and their creator’s death, the adventurous

trio was miserably exhumed by Walter Shute, writing under the pen-name

Gordon Maxwell, in five BFLs published intermittently from 1925–1929; the

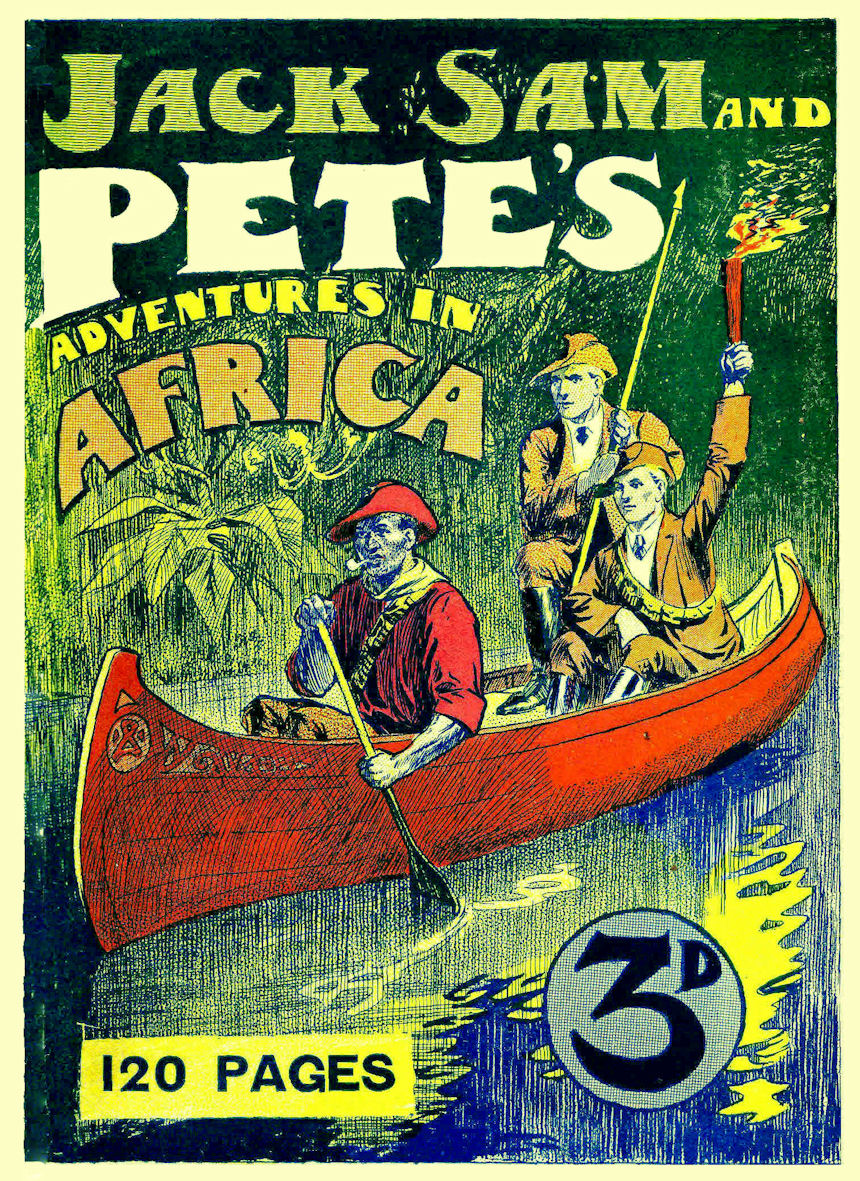

comrades’ final bow came as late as 1936, when a BFL adapted and revised

four very early original stories under the title Jack, Sam & Pete in

Africa— ironically more or less the same title of issue number one of

the BFL thirty years before.

For thirty-five years—longer even than the lifespans of Hamilton’s Gem

and the Magnet—Jack, Sam & Pete had rollicked and fought their way

across the farthest reaches of the globe, usually on foot or by

boat—sometimes by hot air balloon (affectionately nicknamed ‘De Old Hoss’)—trouncing

bullies and confounding dictators, rescuing political prisoners and

discomforting the proud, not to mention starting a variety of institutions

such as newspapers, a parliament, a school for backward boys, a flying

school, a detective agency and a cinema company along the way. Their

adventures were counterpointed by the sometimes ingenuous, sometimes

ingenious bonhomie of the genial, ever noble and often stubborn Pete, whose

extraordinary physical strength proved to be a useful and an often necessary

deus ex machina, a man who feared only three things in the world:

ghosts, ladies of a certain age (particularly sharp-tempered landladies) and

the possibility of his friend Jack Owen falling in love with a pretty girl

and breaking up the trio to get married. He need not have worried on that

score, for that was accomplished by the passing of time, the disappearance

of a vanished Edwardian world and the changing of youthful tastes. But in

their heyday, they were unbreakable.

That their passing into an almost complete oblivion—together with the

vanishing of their once so popular author’s name—is perhaps the saddest

observation to be made in the history of popular literature of this

country.

Nic Gayle

|